The Inga Tree Model is featured in the United Nations FAO TECA program – Technologies and Practices for Small Agricultural

Title: The Inga tree model: regenerative agroforestry

| Id number: | 10056 | |

| Source: | The Inga Foundation | |

| Language: | English | |

| Date of Publication: | November 2020 | |

| Date of Revision: | April 2021 | |

| Keywords: | Agroforestry, Grassland management, Rainforests, Tropical forests | |

| Categories: | Forestry | |

| Country: | Honduras | |

| Region: | Latin America and the Caribbean | |

Summary

Inga alley-cropping is a system of deep mulching using pruned green leaves from the trees which are contour-planted in hedgerows. Within about 24 months, the Inga trees will have recaptured the site from invasive grasses and will be ready for their first pruning. Following cropping, the trees are left to recover their canopy and are pruned again the following year. The system was rigorously developed and tested during the Cambridge Alley-cropping Projects in Central America (1988-2002) and is now being successfully implemented with over 300 families in northern Honduras. The only inputs required are cheap mineral supplements: Rock-phosphate, Dolomitic lime and K-Mag. The combination of N-fixing trees and these minerals is restoring soil fertility.

Description

Inga Foundation is pioneering the introduction of a revolutionary agricultural system aimed at subsistence farmers in the humid tropics; a sustainable alternative to slash-and-burn. Our mission is to turn the tide of unsustainable destruction; to address one of the world’s massive environmental problems and to remedy the food-insecurity that is its principal cause.

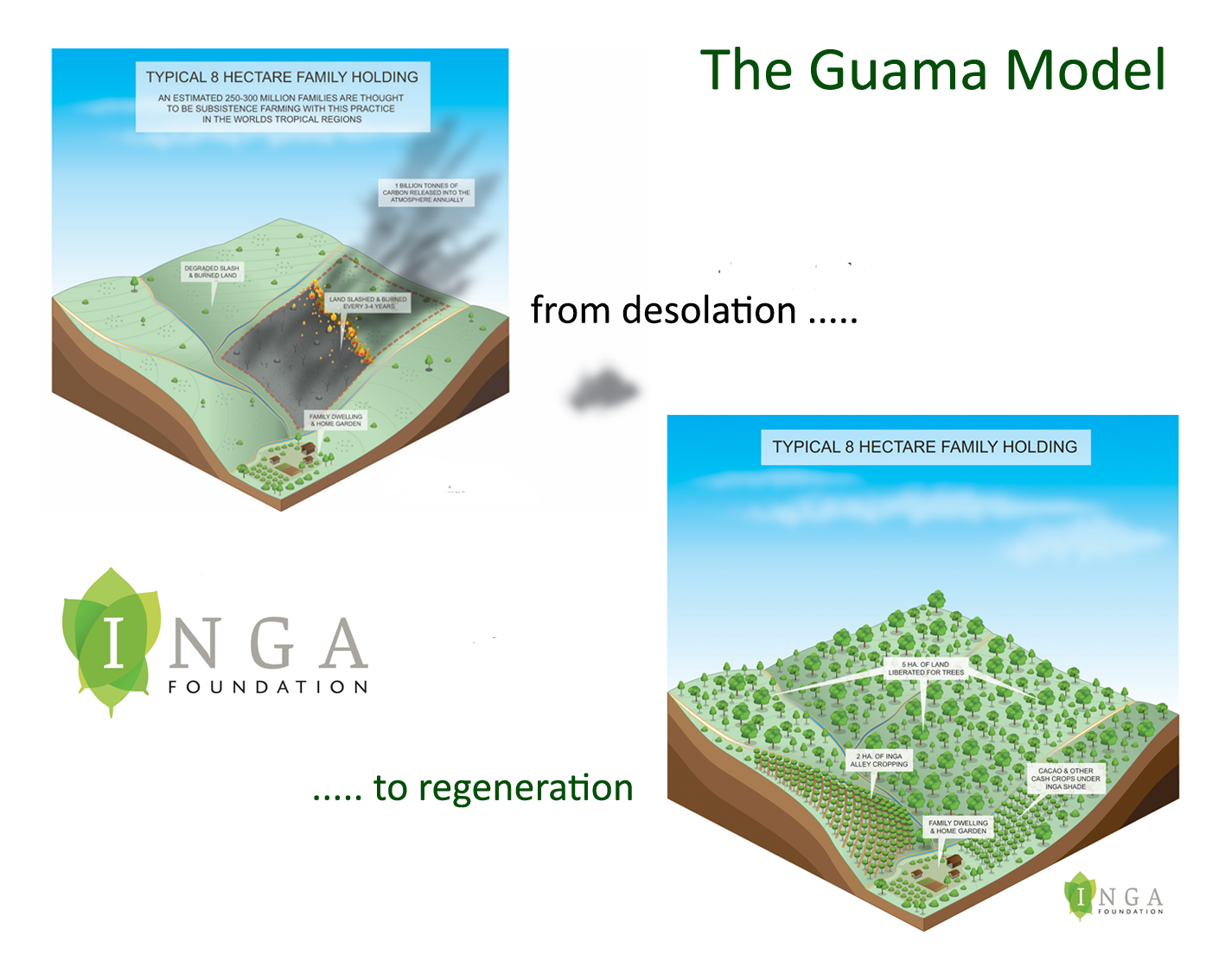

1. Context

Slash-and-burn subsistence agriculture has fed millions of families over past centuries; today it maintains some 250 to 300 million descendant families in poverty; and its widespread failure is an underlying cause of rural-urban migration in the tropics. The consumptive process by which forest cover is converted to invasive grassland, over vast swathes of former tropical forest, is estimated to be contributing between 1 and 2 billion tonnes of carbon (C) annually to the atmosphere; more than all global transport combined. Neither this process, nor the families’ attempts to feed themselves, are sustainable today. Climatic violence is adding an additional dimension of insecurity into their lives.

1.1 Objectives

This practice aims to achieve:

- An end to the destruction of the World’s remaining primary and secondary rainforests by slash-and-burn agriculture.

- An end to the food-insecurity and poverty that is driving that destruction; and to the socially destructive rural-urban migration that results from slash-and-burn’s failure to sustain subsistence agriculture in these environments.

- To introduce and facilitate the adoption of a proven, minimal-input rural livelihood with families who are presently enduring a precarious (and failing) struggle for subsistence by slash-and-burn.

- To promote and further to expand the highly encouraging beginnings of a grass-roots revolution in subsistence agriculture in the World’s rainforest regions.

- Actively to promote the reforestation of those areas of the family holding no longer needed for slash-and-burn.

1.2 How to meet the objectives?

By the introduction of the agroforestry system known as Inga Alley-cropping as the foundation of a low-input, debt-free and scientifically-proven model which is capable of yielding food-security in basic grains, together with a reliable income from cash-crops.

The Guama (the local name for trees of the genus Inga in Honduras) Model results from over 25 years’ research and development, starting with 16 years of research projects led by Cambridge University. Inga Foundation (IF) was founded in 2007 to implement the Cambridge work.

2. What is alley-cropping?

Inga alley-cropping is a system of deep mulching using pruned green leaves from the trees which are contour-planted in hedgerows. In Honduras, the trees are pruned annually, as seen in Figure 6, and left to recover their canopy after the maize has been cropped. It has proved itself capable of achieving food-security in basic-grains for the family, upon a permanent plot which can be located near their dwelling. The system produces a favourite firewood for the kitchen and virtually eliminates the need for weed-control. Additional plots enable the whole family to be involved in their own cash-crop economy; located, perhaps for the first time, on their own doorstep. Weed control is achieved, firstly, by shading under the dense Inga canopy and, secondly by smothering under the resistant mulch.

Figures 1-8 show the sequence of establishing, pruning and managing Inga alley-cropping (Inga a-c) for food-security in basic grains from the starting condition of whole landscapes degraded by decades or more of slash-and-burn. Landscapes such as these are the norm in much of humid tropical Central America. The sequence shows how Inga a-c develops, is pruned and how the crops are grown.

Figure 1. The Rio Viejo sub-catchment of the Cangrejal, Atlántida, Honduras. Impact on the landscape of a century of slash-and-burn.

Repeated slash-and-burn over decades has resulted in a very depleted soil, near-complete deforestation of the landscape and its replacement by invasive grasses, as seen in figure 2.

Figure 2. Near Capapan. Olancho, Honduras. 2008.

Planting saplings of Inga edulis along the contours of the site. 5 000 will have been carried up from the nursery. Contours are found using an “A-frame”.

Figure 3. Cangrejal catchment Atlántida, Honduras.

Figure 4. Cangrejal catchment. Three-month-old Inga saplings beginning the process of site-recapture.

Alley of Inga edulis at two years’ growth and ready for the first pruning. No herbicides have been used. The aggressive grasses dominating the site have been eliminated by shade alone.

Figure 5. Cam projects: San Juan site.

Management of Inga alley-cropping: Hedgerows of Inga edulis undergoing annual pruning. The soil beneath has already been sown with maize.

Figure 6. Inga Foundation’s demonstration farm at Las Flores. Cuero valley, Atlántida, Honduras.

Inga alleys about 10 days post-prune. Maize seedlings just pushing through the mulch. A hundred precent weed-supression achieved firstly by shade and, secondly, by the mulch. Part of a massive haul of domestic firewood stacked in the background; close to the family kitchen where it will be consumed.

Figure 7. Cambridge alley-cropping projects: buffer zone of Parque Nacional Pico Bonito.

Maize developing within Inga alleys. A hundred percent weed-suppression under the mulch; together with physical protection of the soil.

Figure 8. Inga Foundation’s demonstration farm at Las Flores.

Inga is a genus of Nitrogen-fixing legume trees originating in the Amazon Basin and containing over 300 species. The species shown in Figures 3 and 7 (I. edulis) is tolerant of acid soils and is very efficient at recycling essential plant nutrients as well as the Nitrogen fixed in its root nodules. It produces foliage that only decomposes slowly thus giving vital physical protection to the essential surface soil layers from the erosive power of heavy rain and from overheating by direct exposure to solar radiation.

The system develops within about two years and can be maintained permanently thereafter. Small top-up quantities* of rock-phosphate are needed to replace the P removed in the grain; and, in very degraded soils, the trees need supplementary Ca, K and Mg minerals to start the process of site capture from the invasive grasses that typically dominate such sites.

* We apply 50 kg P per ha. in a single application. “Top-up” requires about 10 kg P/ha.

3. Implementation steps

This practice was introduced to farmers by demonstration and farmer-to-farmer extension. Demonstration farms and plots; backed by extension support over the long adoption period (two to three years) provided by local farmers who are employed by Inga Foundation and who are already successfully implementing the system.

3.1 Location

One of the most immediate and valuable of outcomes of sustainability in these cropping systems is that the Inga plots can be located exactly where the family wishes them to be; often this will be close to the family home. This contrasts starkly with the present norm in which the family’s subsistence will depend upon the slashing-and-burning of a new plot every year; or the short-term rotation of slash-burn plots. This, in turn, leads to declining yields and nutrient quality of the staple crops and to a huge labour demand on the family breadwinner to control invasive weeds within the crop. Our own enquiries indicate that the demands of weed-control in degraded sites can involve over 60 man-days of strenuous machete wielding just to produce a low-quality maize crop.

Alternatively, the continual need for fresh vegetation to slash-and-burn each year can involve the breadwinner (almost invariably male) in hours of walking in steep, difficult terrain; often very distant from the family home. We are finding that in establishing the Inga (Guama) alley-cropping system, the plot chosen is usually near the dwelling for convenience, but is usually one of the first that was slashed-and-burned when the family first arrived there, perhaps a century before. The task of the Inga is thus to rehabilitate soil degraded by many repeated slash-burn episodes. A small quantity of rock-phosphate and other mineral supplements applied as the trees develop has been found to accelerate the process of site recapture and rehabilitation; and, moreover, to benefit the subsequent crops. This combination of Inga and cheap minerals has begun to transform lives and livelihoods.

3.2 Benefits of Inga and minerals combination

- The involvement of the entire family in its own livelihood.

The dilemma so often facing the lady of the family is that this year’s slash-and-burn plot is so distant that she can neither take young children with her to assist in its management, nor can she safely leave them alone. If the plot is permanently located close to home, this dilemma is resolved and family cohesion enhanced. - Ease of management.

The easing of labour demands in crop nurture, harvesting and processing (where appropriate); ease of access; freeing the breadwinner’s time for more productive activities other than hours spent in climbing steep terrain. - Food security.

Probably the most important benefit of all. An easing of the anxiety that is inherent in slash-and-burn subsistence agriculture. - Better quality of staple crops.

Higher nutrient content of basic grains (evidence from the Cambridge Inga projects 1989-96). This particularly applies to the quality of protein and the nutritional well-being of children. - Resilience to variations in climate.

Physical protection, by shade or mulch, of the vital upper soil layers and conservation of soil moisture and structure. One of the most important factors here is in the shading of the soil by the mulch and prevention of its becoming overheated and desiccated by solar radiation; or eroded by intense rain. - Domestic firewood produced where it is consumed.

The production of massive quantities of the favourite domestic fuelwood for the kitchen stove; often their only source of heat for cooking. - Security of cash crops.

The ability to guard, protect, nurture and process perennial cash-crops close to the home. We are seeing this in the present projects in which the male breadwinner tends to produce the green pepper crop and the lady of the household invariably takes responsibility for the processing and marketing of the dried, black product. - A hundred percent weed-control.

Achieved, firstly, by the Inga shade prior to pruning and secondly, by smothering under deep, tough mulch after pruning. In almost all cases, maize crops can be produced without the need of a single day’s weeding effort. - Biological pest control.

The well-known ant and wasp associations supported in Inga by the trees’ possession of extra-floral nectaries for these symbiotic insects. Both predatory insects forage for grubs in the tree foliage and in the crops. - Self-reliance and autonomy

The nurturing of the sense of pride and self-reliance that is ingrained in the families that we are working with. Autonomy brought about by minimal dependence on externalities; especially freedom from debt. - Environmental benefits.

Watershed protection; clean water and soil conservation are among these benefits. - The costs to the family. The family’s investment derives from its own efforts in establishing the Inga. They will see no immediate benefits from the system for perhaps two to three years from taking the decision to sign up for the Guama system. The fact that so many are now seeking us out in order to do just that is testament to their faith in what they are seeing in our demo farm and on their neighbours’ farms.

3.3 Present operations in the Cuero and Cangrejal river catchments (Atlantida, Honduras)

Since 2012 we have been able to employ a Forester and an Agronomist to oversee the program of extension work with families in both catchments. Because of limited availability of Inga seed until 2014, together with limited funds to place “boots upon the ground”, we estimated a recruitment rate of 40 families per year; up to about 200 by the end of 2016. This target was passed in mid-2015 amid a growing demand for the system as word spread around the valleys.

A most welcome grant from The Funding Network-SFG enabled us to buy 8 ha. of land at Las Flores in the Cuero valley. In 2019, this demonstration/teaching facility is the living heart of the whole operation. 3.5 ha of Inga alleys and 3.5 ha of Inga seed orchards are now in full production and have transformed the farm’s location. We have also established there a large tree nursery and plant propagation unit. During 2016 to 2017 we were able to add a further 4 ha. which are being reforested as an Arboretum and future seed-source for endangered tree species.

4. The Guama model: an integrated rural livelihood – replicable and debt-free

A single hectare (ha.) has been found sufficient to provide the food security for a family to benefit from a sustainable low-input rural livelihood. The Guama model was developed with local non-Governmental (NGO) partners alongside Honduran farmers to provide typically:

- 1 to 2 ha. of Inga alley-cropped (Inga a-c) basic grains; (e.g. maize, beans)

- 1 to 2 ha. of Inga alley-cropped cash-crop cultivars (e.g. vanilla, black pepper, turmeric);

- 1 to 2 ha. of low-maintenance fruit trees, (e.g. cacao, avocado, citrus) 2 to 4 ha. of formerly degraded land for reforestation and carbon-capture.

Figure 9. shows the same system (Inga a-c) managed for cash crops (in this case, the production of black pepper and turmeric). This is component two of the Guama Model.

Figure 9. Las Flores: Pepper (Piper nigrum) on living stakes of Gliricidia sepium within Inga edulis alleys. The Pepper is interplanted with developing Turmeric (Curcuma longa) and Plantains (Musa sp.).

©The Inga Foundation

Figure 10. shows the association of Inga and Cacao. In this case, not in a-c configuration. much more widely-spaced Inga as shade and as a source of N for the Cacao. This is component three of the Guama Model.

Figure 10. CURLA site: Young Cacao developing beneath the shade of Inga edulis. Weed-control here is largely achieved by shade. This site had been dominated by invasive grasses prior to its recapture by the Inga.

©The Inga Foundation

The model assumes a holding of about 8 ha and is completely flexible; a family can adopt any component, or combination of components, on any area, that it wishes.

Inga a-c, supplemented by rock-phosphate, emerged from the Cambridge Projects as the only system holding any promise of sustainability. In 2014 IF made the ground-breaking discovery that this combination, together with light applications of other mineral nutrients (Dolomite and Magnesium/Potassium sulphates), is capable of restoring the fertility of soils degraded by over 100 years of slash-and-burn. We know of no other system capable of this; and this has begun transforming lives, livelihoods and landscapes.

Figures 11 and 12 show steps in using Inga as a ”framework” species for site-recapture and reforestation (component 4 of the Guama Model)

Figure 11. Future arboretum. Las Flores. San Marcos, Cuero valley. Reforestation of degraded pasture. March 2017. Newly-purchased land adjacent to the Inga Foundation demonstration farm at Las Flores. Inga edulis and I. oerstediana planted as “matrix” or framework species; later to be interplanted with cacao and a wide mixture of rain forest trees.

©The Inga Foundation

The same slope in May 2020. Seen from a distance, it resembles a low-stature forest. It functions as an agro-forest and arboretum for rare and endangered tree species. In time, the inter-planted trees will overtop the Inga spp., branches of which will be lopped sporadically to allow light onto the cacao. A spring has started flowing close to the location of the lower lady in figure 11 (above).

Figure 12. The arboretum at Las Flores three years later.

©The Inga Foundation

Figure 13 below illustrates the model in the landscape. Carbon-emission avoidance and capture of atmospheric Carbon (C) have been estimated for the whole program; and annual data for one family adopting the model are included here covering the first 12 years following adoption.

Since 2012, IF’s Land for Life Program, now (May 2020) involves around 250 families; the Program has sequestered over 300 000 tonnes of atmospheric CO2; a figure that will reach over a million tonnes by the end of 2025:

Figure 13. The Guama Model: Achieving food-security on soils degraded by centuries of slash-and-burn; re-invigorating the rural economy; restoring habitat and transforming degraded soil at landscape-scale. This strategy is neither cheap, nor quick, nor easy. It is, however, permanent. No family goes back to the old ways.

The model assumes the average holding of 8 ha. and reforestation of 1 ha. annually from year 3. The family’s total net accumulated Carbon-capture and emissions avoidance exceeds 1 100 tonnes by the end of year 12; and will continue to accumulate for a century or more.

5. Scope and purpose: cash-crops

A wide diversity of cash-crop cultivars have already been successfully proven in Inga alley-cropping during the Cambridge projects. The mulching system eliminates the need for physical or chemical weed-control and provides the biological conditions for reliable cash-crop production. Whilst yields might not match those of large-scale plantations, an acceptable crop can be produced on minimal external costs. The investment derives from the family’s own effort and care; not from crippling external finance. Broad strategy is to produce those cash crops that already have a local market and are fitted to the logistics of reaching those markets in marketable condition. Black Pepper, Curcuma, Maracuyá (Passiflora sp.) and Vanilla are good examples.

The long-term objective is to establish with the families the basis for the production, quality control and local marketing of cash crops; to the point at which economies-of-scale begin to exert a positive influence on both logistics and the families’ collective bargaining power.

This phase is seen as mainly occupying the later 5-year phase of the 10-year overall plan. Alley cropping for food-security and the slow replacement of slash-and-burn were given priority within the first five years.

6. Wider strategy: these projects as models for the Central American Region

Inga Foundation’s strategy is to concentrate effort and resources into the area where we are presently established. The overall objective is that enough families can be seen successfully implementing and replicating the Guama Model such that it will begin to replicate itself spontaneously. The whole area may serve as a model of resilient best-practice for the whole humid Central American/Caribbean region in a time of climate-change. IF’s role in teaching these techniques has already attracted national (Honduran Gov’nt) and regional (PARLACEN) attention.

This strategy reflects our view that 200+ families, thus concentrated in these two river catchments, and transforming both their own environment and economies, would be sufficient to demonstrate the Guama Model’s capacity for massive change at landscape scale; together with massive sequestration of atmospheric Carbon. This is aimed at those major international decision-makers who will need to see the model working at such scale.

7. Resilience to climate change

The ability of Inga alley plots to withstand the worst effects of climatic violence was demonstrated during the 2015-16 El Niño events; and again during the drought of February-April 2019. The mulch proved itself resilient to both heavy rain and direct solar radiation. Evaporation from the vital surface soil is avoided beneath the deep cover. We have seen examples of basic grains planted in the alleys after the last rains in early February 2019 growing to productive maturity during April or May without a single drop of rain having fallen. They have matured on residual soil moisture retained by the soil’s enhanced organic matter and protected by the mulch.

The result of these events has been a huge surge of demand from these farmers’ neighbours for the system. Today, hundreds of families in these two valleys are asking for help.

8. Validation of the practice

To date (May 2020) IF’s Land for Life Program is succeeding in convincing all who have witnessed it at first-hand. About 250 families have Inga alley-cropping in various stages of development or use.

Many families now have multiple plots for rotation of basic grains and/or cash-crops. Since the Program’s inception in 2012, around 4 million trees have been planted in various configurations, including over 250 000 grafted or hybrid Cacao; a similar number of other fruit trees (mainly Rambutan); and about 100 000 fine timber tree saplings. By the end of 2020, our Carbon model estimates that the Program will have been responsible for the sequestration/avoidance of over 392 000 tonnes of atmospheric CO2; growing to over 522 000 tonnes by the end of 2021.

9. Minimum requirements for the successful implementation of the practice

At its present level of funding, Inga Foundation cannot support any expansion in its field operations. The original objectives of the Land for Life Program are being met and we can expect to see them achieved by the end of 2021; or, at least, have them well advanced towards achievement.

Any further expansion of these operations will require substantial core and operational funding, together with additional senior personnel. Sufficiently funded, Inga Foundation could continue its present role in the two valleys whilst shifting its “centre-of-gravity” to training and demonstration for a wider regional role. Ongoing field operations are useful as a means of training extension workers as well as fulfilling their obvious value in transforming lives and livelihoods locally, as intended.

10. Agro-ecological zones

- Tropics, warm.

- Tropics, cool/cold/very cold.

- Subtropics, warm/mod cool.

11. Related/associated technologies

- Good practices of agro-forestry systems: the Kuxur rum system; ID 8852.

- Intensive agroforestry system: ID 7510.

- Agroforestry coffee cultivation in combination with mulching, trenches and organic composting: ID 8928.

- Production of tree seeds for agroforestry: seed sourcing: ID 7966.

12. Objectives fulfilled by the project

12.1 Women-friendly

Assistance in-kind given to single-parent families to help establish and bring to first-use Inga alley systems. Inga Foundation has a long-term policy of not donating funds to families; we do, however, contribute “Boots on the ground” as Technical Assistance (TA).

12.2 Resource use efficiency

Erosion protection giving clean and consistent water flows in streams. More water held in the soil; and for longer periods.

12.3 Pro-poor technology

Massive transformations in the family’s income with minimal dependence upon externalities. Higher nutritional value of basic grains from the Inga system and a more diverse diet produced without agrochemicals.

https://teca.apps.fao.org/teca/en/technologies/10056